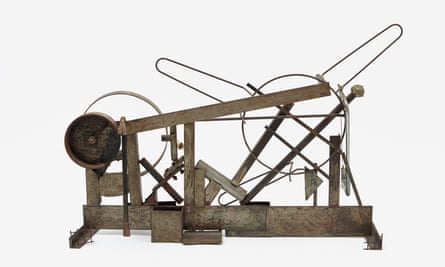

In the late 1980s, one of Britain’s most acclaimed painters, Sir Frank Bowling, made his only foray into sculpture: welded steel abstractions were fashioned from stumpy steel bars, free-ranging metal curlicues and spirals of mesh left in his studio yard by the engineering firm next door. Originally conceived to be shown alongside his paintings, they are now the centrepiece of the first exhibition highlighting his canvases’ less-considered sculptural dimensions. For the past 30 years, though, these pieces were strangers to public view, arranged companionably around the flat in Pimlico, central London, he shares with his wife, the textile artist Rachel Scott.

“[My sculpture] King Crabbé was halfway up the stairs,” Bowling says. “Bulbul was next to the TV and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat was in the living room, capped with a pith helmet and a hand-knitted sock. They always seemed to gather things: postcards, woolly animals and drawings. One has a jemmy and a hacksaw.” Unfortunately, some works from the series no longer exist: left outside the studio, they were stolen and probably sold as scrap.

That Bowling’s sculptures should become almost part of the furniture is perhaps no surprise. First, real life often has a direct role in his painting, with daily flotsam embedded in many intensely hued abstractions. “I’m moved to chuck in detritus and watch it swim and settle. It makes me feel I can get to a whole vision of what I’ve passed through in life,” he says.

Yet the sculptures’ casual treatment also speaks to how overdue recognition of the Guyana-born artist has been in the UK. Although he was a leading talent among an art school cohort that included David Hockney, his career has been more celebrated in abstract art’s flag-flyer, New York. As both an art critic and practitioner, in the 1960s and 70s Bowling fuelled debates around Black art there, including abstract art’s potential to speak of Black identity. Back in the UK, he was an outlier among his pop art-dominated generation. In the past few years, however, things have changed fast for the 88-year-old, between becoming the first Black Royal Academician in 2005 and his lauded Tate Britain retrospective in 2019.

While it’s Bowling’s more overtly political paintings that have garnered particular attention, his engagement with his medium has many dimensions. For the curator Sam Cornish, the sculpture exhibition will be a chance to see Bowling’s “complicated and contradictory work in a more rounded way”.

A core focus of the show is the artist’s lifelong interest in geometry, beginning with his cabinet-maker uncle in Guyana, who taught him to make “rock-solid furniture” by embedding circles in squares, and later sharpened by encounters with the work of Mondrian and Caro. In earlier paintings such as Sasha’s Green Bag, with its gridded surface, and in Ancestor Window, with lengths of foam beneath pigment, there’s a concern with structure that the steel geometries draw out. Recent works where paint holds everything from glitter to acupuncture needles share an attitude with Bowling’s sculptures, too, trying out ideas with what comes to hand. “Maybe I have got more playful in the years since I made these sculptures,” he says. “Growing old has given me a new impetus to take risks. I’m looking for that special thing you haven’t seen before that you just catch out of the corner of your eye.”

It’s about geometry’: Bowling on his art

Mummybelli, 2019

“It’s a diary of my last trip to New York in 2018. The warm welcome note from a gallerist is there in the painting along with the bunch of roses that he sent us, all drenched in gel and gold powder colour. I’m using techniques that I’ve used for decades: staining, dripping, pouring, embedding this and that into the canvas.”

Hrund, 1988

“As a student, I avoided sculpture. As I became more involved in painting, I realised that geometry was a vital element. That structuring ineluctably drew me to sculpture.”

Bulbul, 1988

“Back in 1988 a curator asked whether I was interested in showing sculpture alongside painting, so I thought: ‘Well, why not make some?!’ The sculptures are made of scrap metal. Just as you see them. Things that took my fancy.”

Pendulum, 2012

“In both the paintings and the sculptures it’s about geometry – the way that squares and circles and triangles interact to create stability in form.”

Ancestor Window, 1987

“This is from the Cathedral series. The pattern is laid out using strips of acrylic packing foam around a design based loosely on an illustration in the Handbook of Ornament by Franz Sales Meyer. The heavily built-up surface carries a lot of paint colour, but you also have this very strong underlying geometry.”

Frank Bowling and Sculpture is at the Stephen Lawrence Gallery, London, until 3 September.